The Sacred Work

The veneration of sacred Scripture was a central feature of medieval culture. Scriptural reading was a staple of the medieval cleric’s literary diet, and cathedral art depicted scenes from the Bible for the benefit of illiterate parishioners. In order to clarify ambiguous passages in the Bible, Christian educators offered interpretations which, when approved as orthodox teaching, were handed down as a part of sacred Tradition. Within the first few centuries of the Christian era, an abundant literature of interpretation arose, and over the course of later centuries the doctrines of the early theologians were sifted to determine whether they qualified as orthodoxy. In the twelfth century, theologians compiled these orthodox interpretations into a collection known as the Glossa ordinaria, or "Standard Gloss," which a reader of Scripture could consult with confidence when in doubt over the meaning of a given passage.

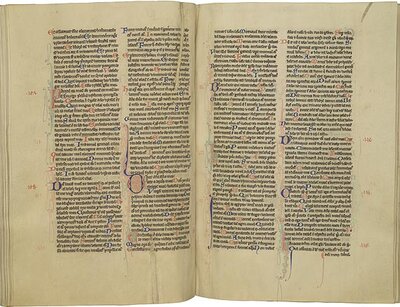

Ninth Century Fragments

Although Christians regarded Scripture with the highest respect, they did not venerate the physical book itself in perpetuity. When a Bible became worn from use, a new copy would be made, and the old one might be recycled—perhaps cut up and used to reinforce the binding of a new Bible. This leaf, which has been cut in half, was salvaged from the binding of another book, where it appears to have been used for pastedowns. The Bible from which the leaf was cut was clearly a very large one. Dating from the ninth century, this bisected leaf is among the oldest Latin artifacts in the holdings of Cornell’s Rare and Manuscript Collections.

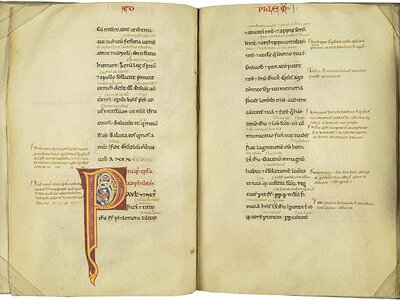

English Bible

Established in the fourth century, largely by St. Jerome, the Vulgate Bible was so named because it was popular (the Latin vulgus means "the people"). The copy shown here displays several characteristics of the standard Vulgate text adopted in the schools of Paris during the thirteenth century, such as the order of the books and the way they are divided into chapters. Shown are Psalms 107–116, as the rubricated medieval Arabic numerals in the margins indicate. Among the red and blue initials in the text, the large capitals mark the beginning of a new Psalm, and the smaller capitals introduce a new verse. Medieval scribes used these colored letters instead of indentation to start a new paragraph.

Origen of Alexandria

Writing in the third century, Origen of Alexandria was one of the early commentators on Scripture. Although he was highly respected during his lifetime, his name came under a cloud centuries after his death when Church councils refined the boundaries of orthodoxy and decided that several of his views were heretical. For example, he believed in the pre-existence of souls and thought that eventually even the Devil’s sins would be forgiven. While the Church condemned these views, later clerics preserved much of Origen’s legacy as sound and inspired teaching—particularly his commentaries on Scripture, as indicated by this stately manuscript, copied in Italy ca. 1100.

Purchased in 1885 for A.D. White.

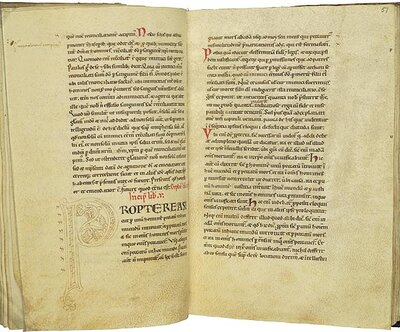

Commentary on St. Paul’s Epistles

This commentary on the Pauline epistles experiments with a format that was intended to ease the burden on the reader. The page is open to the beginning of the commentary on St. Paul’s letter to Titus. Here the text of the Bible itself appears in large characters in a central column on each page; brief interpretive comments, or "glosses," are written between the lines, while longer remarks appear in the margins. The comments correspond to those of the Glossa ordinaria, or "Standard Gloss" of interpretations of the Church fathers that was compiled in the twelfth century.

Purchased in 1877 by A.D. White.