Appetite for Destruction

For every medieval manuscript that has survived into modern times, many others have been destroyed. We know this partly from the numerous fragments that survive, representing books that were once whole. The causes of destruction were various. Fires engulfed libraries and obliterated untold numbers of books. Political upheavals, such as the French Revolution, which sought to blot out all vestiges of the hated era of "feudalism," carried away many others. Thieves and collectors have mutilated decorative manuscripts by removing the artwork. Yet perhaps most manuscripts were lost to less dramatic causes, such as neglect and poor storage conditions, which exposed books to damp, rot, and insects. Renaissance humanists in search of rare classical texts describe visits to monasteries where they found heaps of books moldering away, utterly abandoned. One other cause of destruction was recycling. Since parchment was expensive, an old book might be scrapped and its writing erased so that a new book might be written on its parchment, or it might be cut up for use in bindings.

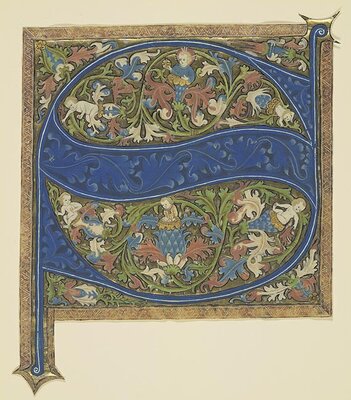

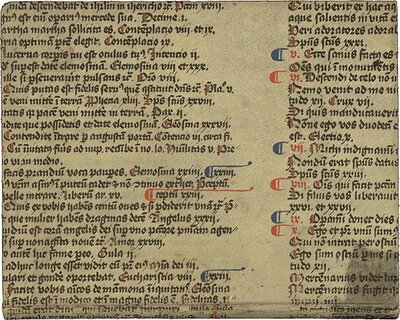

Mutilation

These illuminations were removed from choirbooks, as indicated by the text on the back of the fragments. It is uncertain whether they were taken from manuscripts that were mutilated in the process, or whether they were salvaged from manuscripts that had been slated for recycling. Liturgical texts were often scrapped when they were considered outmoded.

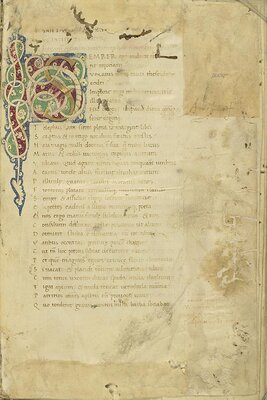

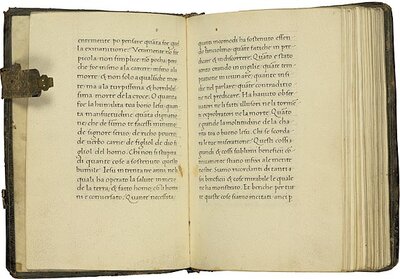

Eaten by Worms

Wormholes are visible in these two examples, indicating that insects have feasted upon them. The copy of Juvenal is so badly worm-eaten that some of its text has been lost, and a strip of parchment has been added to mend the page.

The vernacular book, which offers meditations on the Passion of Christ, has fared better. Although two small wormholes near the top have left the text unimpaired, the book has apparently preserved the crushed remains of an insect, visible in the inner margin of the left page. The term "bookworm" generally refers to the larvae of a certain family of beetles (Bostrichidae), but these are not the only insects that destroy books; other offenders include moth larvae, silverfish, cockroaches, and booklice.

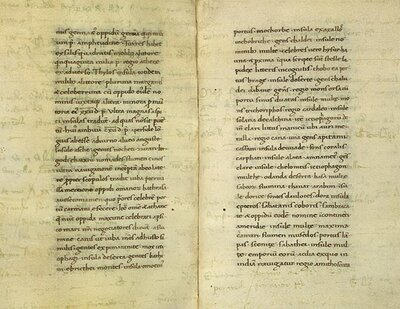

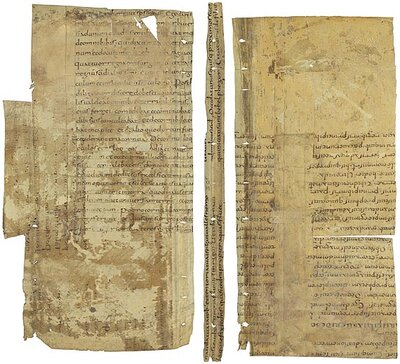

Palimpsests

Manuscripts that have been written upon more than once are known as palimpsests (from the Greek palimpsestos, "scraped again"). The ink of the original text has been scraped away to make room for the new text, yet a dim after-image of the original remains. A careful look at the margins will reveal a cursive script, apparently in a vernacular language rather than in Latin, although the words are too faint to identify the text accurately. Ultraviolet light can sometimes help to bring out an underlying text.

Purchased in 1885 for A. D. White.

Recycled Parchment

Despite their reverence for Scripture, medieval readers did not worship the physical book– at least, book-owners had no qualms about tearing up an old Bible and reusing the parchment in bindings. The three fragments from a ninth-century copy of the Bible on display have been arranged according to their disposition in the binding of a book, where they were used as pastedowns and as backing in the spine. A leaf from another manuscript, which offers a chapter-by-chapter summary of the four Gospels, was used as a cover for a 16th-century printed book.