Schoolbooks

The centrality of sacred Scripture in medieval culture made reading a vital part of education. To advance understanding of Christian teachings, the Church organized a system of education that enabled its clerics to better spread and interpret Christian beliefs. Taking the liberal arts curriculum of the ancient world as a model, the Church used secular texts to educate its intelligentsia.

Until the twelfth century, monasteries played the primary role in copying and preserving non-religious texts. From the twelfth century onwards, non-monastic cathedral schools became the leading institutions for education. By the 13th century, some cathedral schools had developed into universities, creating a new educational model known as "scholasticism." The scholastic university system lasted into the early modern period. During the Renaissance, however, Italian humanists called its methods into question, reacting against the universities as overly parochial and restrictive in their outlook and aims.

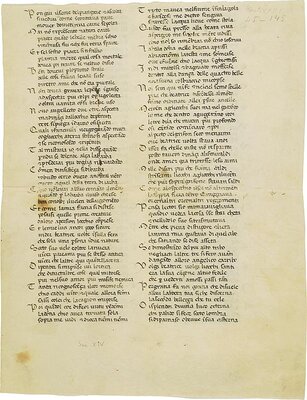

Grammar

Amo –mas –mat… Medieval students had to begin with the basics: conjugating Latin verbs. This well-worn textbook attests to the centrality of grammar in the medieval schools. Grammar, along with rhetoric and logic, formed the "trivium," which was the literary component of the liberal arts curriculum that the Middle Ages inherited from Antiquity.

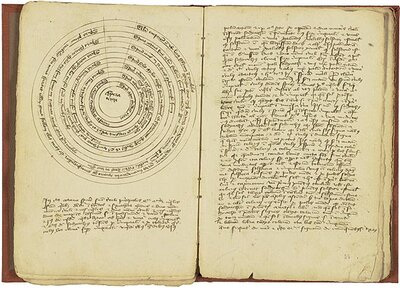

Computus

In addition to the trivium, four other liberal arts constituted the mathematical branch of advanced studies, known as the "quadrivium": arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. This manuscript, which features an astronomical diagram of the planets encircling the earth, is a computus, or text designed to facilitate calendrical calculations. The geocentric diagram is included to provide theoretical context for the practical exercises.

Purchased in 1888 for A.D. White.

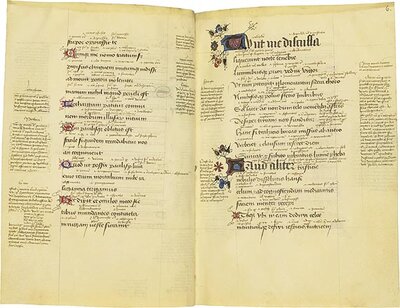

Boethius

The Consolation of Philosophy, by the sixth-century philosopher Boethius, was a standard text in medieval schools. One reason for its popularity among educators was that it combined the two halves of the liberal arts curriculum: the literary trivium and the mathematical quadrivium. The text also demonstrated how philosophy could assist in the study of theology. This deluxe copy, written in the cursive Gothic, or "bâtard," script that was popular in 15th-century France, is heavily glossed, suggesting that someone used it as a study-text.

Purchased in 1885 for A.D. White.

Quodlibeta

During the era of scholasticism, which began ca. 1100, philosophy became the handmaiden of theology. A common exercise in the schools was the quodlibetal disputation, in which a master would be given a theological question that he had to answer using philosophical arguments. "Quodlibet" is Latin for "anything at all," indicating that the theologian had to be prepared for a no-holds-barred battle of wits. The debates were recorded by scribes and published in collections. This manuscript contains the collection of quodlibetal disputations by the late 13th-century theologian and bishop, James of Viterbo.

Purchased in 1893 for A.D. White.

Dante

Late in the 13th century, the Florentine poet Dante Alighieri acknowledged the dominance that scholasticism had attained by incorporating the fruits of scholastic philosophy into his monumental vernacular epic, The Divine Comedy. This leaf from the Purgatorio describes the pageant of salvation in the coded language of allegory.

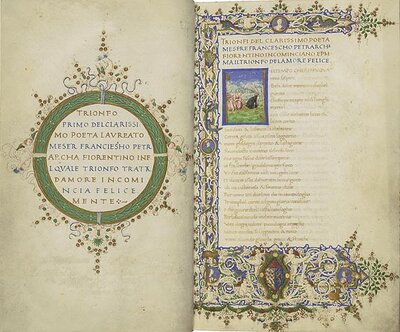

Petrarch

The scholastic method, with its emphasis on Aristotelian philosophy, became so dominant and entrenched in the university system that it excited a reaction. This reaction was spearheaded in the 14th century by Francesco Petrarch, the Florentine humanist known as the Father of the Italian Renaissance. Petrarch was instrumental not only in challenging the dominance of scholasticism, but also in furthering the prestige of vernacular literature, as this deluxe manuscript of his Tuscan poetry demonstrates.

Bequeathed in 1904 to Cornell University Library by Willard Fiske.

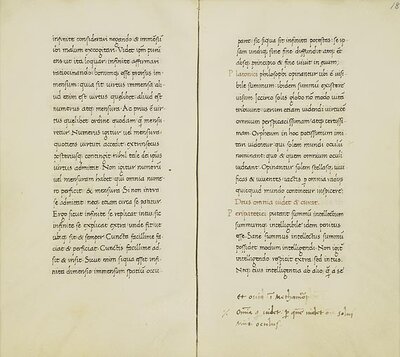

Platonic Wisdom

Humanists after Petrarch furthered the challenge against the Aristotelian philosophies of the scholastics by basing their own philosophies on the work of Aristotle’s teacher, Plato. This fine manuscript, The Five Keys of Platonic Wisdom, is autographed by the 15th-century Platonist Marsilio Ficino, whose hand appears in the margins.

Purchased in 1885 for A.D. White.