Churchbooks

Medieval Christianity was concerned with far more than the study of sacred Scripture. The Church also venerated the saints as models of the Christian life. Thus, the Church depended upon hagiographical and liturgical texts for its daily functioning, as well as administrative documents issued by bishops. In the Latin West, the head of the Church was the bishop of Rome, that is, the pope. In his documents he styled himself servus servorum dei — "the servant of the servants of God" — in memory of Christ’s command that "the greatest among you must serve the least."

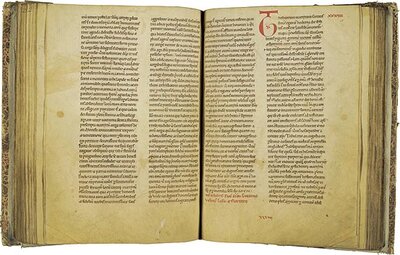

Lives of Saints

In the medieval Church, the veneration of the saints enjoyed almost as much attention as the books of Scripture themselves. This twelfth-century German manuscript, as big as a Bible, provides readings from the lives of the saints over the course of the year. The celebration of saints’ feast days was an important part of the annual cycle of the liturgy.

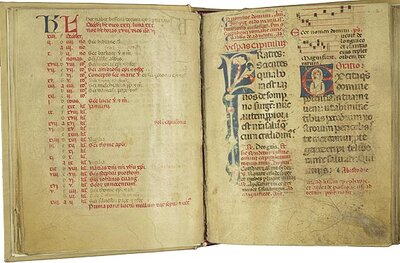

Daily Mass

The liturgy was the communal observance of formal prayers–especially the Mass–in which priests re-enacted the sacrifice of Christ in the sacrament of the Eucharist. Manuals like this one provided the daily formula for the liturgy.

This well-worn manuscript obviously saw heavy use. The page on the left presents the end of a calendar that indicates which saints to commemorate on any given day. Many of the saints were martyrs from ancient times, but the calendar also includes more recent saints, including St. Thomas Aquinas, who was canonized in 1323, making him the newest saint at the time this manuscript was copied.

Purchased in 1885 by A.D. White.

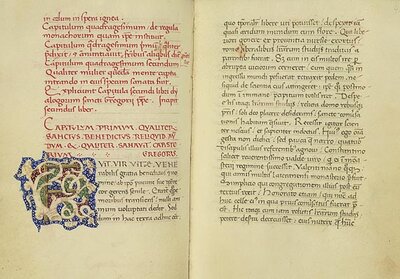

St. Gregory the Great

Pope Gregory I (590—604), also known as Gregory the Great, was the first monk to be elevated to the papacy. St. Gregory exemplified the ideal that the pope should be the "servant of the servants of God" — indeed, he was the first to use this formula. A member of the Benedictine Order, Gregory presented a hagiographical account of its founder, St. Benedict of Nursia (ca. 480—ca. 550), in his Dialogues.

This elaborate fifteenth-century copy of the Dialogues is open to the beginning of Book Two, which contains the life of St. Benedict. The great achievement of St. Benedict was to compose a Rule for monks that provided discipline without imposing excessive austerities. The Rule of St. Benedict is in fact a model of balance: it gives equal weight to prayer, manual labor, and reading in the monastic regimen. Due to St. Benedict’s insistence on the importance of reading, the Benedictines developed copy-rooms, known as scriptoria, in which they preserved religious texts. They also preserved many secular classical texts that would otherwise have been lost during the most chaotic period of the Middle Ages.

Purchased in 1903 for A.D. White.

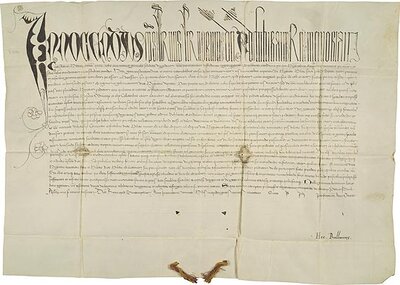

Papal Bull

Popes issued documents, known as papal bulls, in their administration of Church affairs. This papal bull, distributed by Innocent VIII in 1488, asserts the pope’s privilege of appointing the Master of the Spanish Order of St. James of Compostella, the pre-eminent pilgrimage site in Europe. The elongated characters of the heading, "SERVUS SERVORUM DEI," refer to the pope, who in his governance of the Church was to serve God’s servants rather than flaunt his power. By the time of Innocent VIII, however, the papacy had lost sight of the ideal of service that St. Gregory the Great had inculcated. Innocent VIII was more concerned with raising money to pay off debts than with guiding the moral life of the Church — so much so that at one point he even pawned the papal tiara. His conduct was typical of the papacy during the Renaissance, whose abuses led to the Reformation inaugurated by Martin Luther.