The Written Word

At least two native groups in the Americas developed systems for record-keeping before the Europeans came. The Mayas in Central America had a true system of writing. Those familiar with the language and versed in their hieroglyphs can read the inscriptions on their monuments. The Incas in the Andes of South America kept records by a system of knots in strings called quipus. Though they are not completely understood, scholars believe they were used for both accounting and as mnemonic devices, or aids to memory. The Plains Indians in North America used pictures to illustrate significant events of a particular time period. Surviving “winter counts,” pictures painted on hide, depict such occurrences as epidemics, battles, and droughts. Other North American groups painted and carved images to remind them of events or numbers. Most records of their histories were oral, stories repeated again and again from generation to generation so they would not be forgotten.

Faced with the need to communicate, missionaries addressed the challenge of transcribing Indian languages to written form soon after they began to Christianize Native Americans. These early attempts were largely for the benefit of Europeans, but the emphasis soon turned to the reproduction of religious texts in local languages. Missionaries struggled with standardizing transcriptions of unfamiliar sounds. While usually employing the standard Latin alphabet, they also came up with a variety of other creative solutions to write Indian languages. Many native Americans soon learned to read and write.

Written Indian languages made the transition from religious to secular with varying degrees of success. In the United States today, using language immersion and bilingual education programs, tribes struggle with the challenge of sustaining native languages in both oral and written forms.

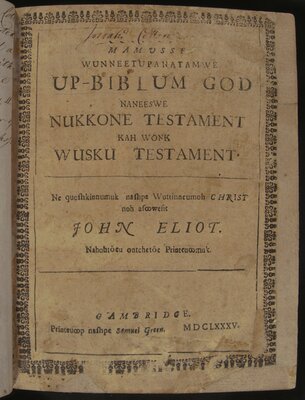

John Eliot. Bible. Mamvsse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God. Cambridge: Printeuoop nashpe Samuel Green, 1685.

John Eliot (1604-1690), known as the “Apostle to the Indians,” translated into the Natick dialect the first Bible in any language published in North America. He was ably assisted in this effort by several Indians, including Harvard-educated James Printer and the preacher John Nesutan. First issued in 1663, many copies of the original edition were destroyed during King Philip’s War in 1675.

Eliot was also responsible for establishing towns for “Praying Indians,” converts who could live together, free from the influence of local settlers in Massachusetts. Natick was established in 1651, and at least ten others followed. By 1674, the census of “Praying Indians” was 4,000. The towns were largely destroyed during King Philip’s War.

Book of Marriages from the Convent of Quauhquechola, 1620-1639.

Located in the Mexican state of Puebla, the Convent of Quauhquechola may be the one established by the Franciscan friar Juan de Alameda, in what is now called Huaquechula, sometime between 1530 and 1570. Alameda, who was also an architect, is often credited with the design of the convent. This manuscript, written in the Nahuatl language, is a record of local marriages.

Cherokee Singing Book. Printed for the American Board of Com-missioners for Foreign Missions. Boston: Alonzo P. Kenrich, 1846.

Sequoyah (1760-1843) created the Cherokee syllabary as a cultural bulwark for his people, to lessen the influence of their white neighbors. A syllabary is a set of written characters, each one representing a syllable. By 1821, Sequoyah had reduced the number of symbols needed to produce whole Cherokee syllables to eighty-six characters, and the Cherokee Tribal Council formally adopted the system shortly after. Using the syllabary, the council started its own newspaper, The Cherokee Phoenix and Indian Advocate, in 1828. The syllabary proved easy to learn, promoting a high degree of literacy among the Cherokee throughout the 19th century in both North Carolina and Oklahoma. The first sixteen pages of this Singing Book contain instructions in music, while hymns in Cherokee comprise the rest.

Fidelia A. H. Fielding. Diaries and Religious Texts Written in the Mohegan Language, 1902-1904.

Fielding (1827-1908), the last speaker of the Mohegan-Pequot language, lived at Mohegan, near Norwich, Connecticut. She kept the Mohegan of her childhood fresh by speaking with her sister, or talking to herself. In the later years of her life, she cooperated with anthropologist Frank G. Speck, providing him with a lexicon of 446 Mohegan-Pequot words, and narrating several Mohegan tales. During the years 1902 to 1904 she made occasional notes in her diary, written in Mohegan, along with transcriptions of religious texts in that language. Today the Mohegans and Pequots of Connecticut draw on the Fielding-Speck collaboration and her diaries to study their language.

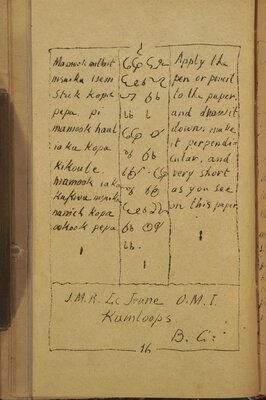

Kamloops Wawa. Kamloops, British Columbia, 1891-1923.

Published by Father J. M. R. Le Jeune (1855-1930), an Oblate missionary in the interior of British Columbia, the Kamloops Wawa was a mimeographed newsletter offering "Indian news" in three parallel languages: English, a transliteration of Chinook jargon, and the jargon written in Duployan shorthand. Due to the Wawa’s wide circulation, both Indians and non-Indians learned to read and write this form of shorthand, developed by the Duployé brothers in France. It also encouraged the use of the Chinook jargon, a trade language combining words and language structure drawn from Pacific Northwest tribes with English and French terms. Local Indian tribes, who spoke a variety of languages, used the jargon to communicate with each other as well as with traders.

Okodakiciye wakan tadowan kin. Hymnal According to the Use of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Mission Among the Dakotas. New York: T. Whittaker, [1885].

This hymnal, first published in 1874, was written in the Yankton dialect of the Dakota Indians. It was obviously cherished. Its owner covered it with hide and decorated it with dyed porcupine quills.

Quechua Catechism. Chile, 19th century.

Originally bound in hide, this pictographic catechism was created to teach religious ideas to parishioners from the Quechua-speaking area of the Andes who could not read. A memory aid rather than a writing system, the pictographic script shown here is based on European iconography. A line at the top, written in the Quechua language, introduces each page.

According to a translation published by Barbara H. Jaye and William P. Mitchell, the first line of the Apostle’s Creed shown here reads:

Line 1: I believe in God, the Father Almighty, creator of heaven and earth 1. I believe in [kneeler]; 2. God [standing man with cloak and halo in oval]; 3. the Father Almighty [enlarged version of preceding God symbol]; 4. I believe in [kneeler]; 5. Jesus Christ [crucifix]; 6. I believe in [kneeler]; 7. heaven [ornamented circle with seated God]; 8. and earth [church in circle]; 9. the all powerful God [standing man with cloak and hat in oval]; 10. Father [man holding child or soul]; 11. creator [artisan with hammer].

Mort Walker. Beetle Bailey. Translated by Martin Cochran into the Cherokee language. Tahlequah, Oklahoma: Cherokee Bilingual Education Program, n.d.

The Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma has been involved in bilingual education programs since the 1960s. Today, there are approximately 10,000 speakers of Cherokee enrolled in the Cherokee Nation. The Bilingual Education Program encourages literacy in Cherokee among the young with publications such as this comic book.

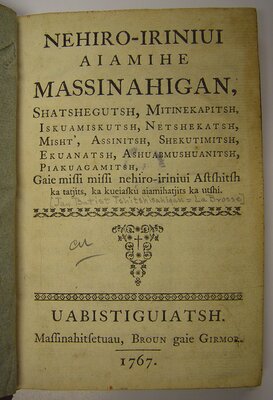

Jean Baptiste de La Brosse. Nehiro-Iriniui Aiamihe Massinahigan Uabistiguiatsh [i.e. Québec]: Massinahitsetuau, Broun Gaie Girmor, 1767.

La Brosse (1724-1782), a French Jesuit missionary, was a forceful advocate for the Montagnais (Innu) and Abenaki peoples in Canada. As a missionary to the Montagnais, he embarked on a successful program of literacy for those in his parish. This prayer book in Montagnais was the first book published in an Indian language in Canada.