Anthropologists & Native Americans

Starting in the late 1960s, Native Americans began protesting their treatment by anthropologists as objects belonging to a distant past. Where were the “anthros,” the protesters asked, when the government was pursuing destructive assimilation policies? How were native groups benefiting by their cooperation with these scholars?

Anthropology emerged as a distinct field of intellectual inquiry in the United States in the late nineteenth century, a time when the future of Native Americans seemed dubious. Indian tribes, as such, would soon be gone, anthropologists reasoned, and scientists and explorers should learn as much as possible about their customs and crafts before they vanished. In the scramble to document before it was too late, some anthropologists had little regard for native sensibilities, or for tribal desires to keep their ceremonies private and their dead buried in undisturbed graves.

Museums worked hand in hand with early anthropologists. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, they made concerted efforts to collect ethnographic and archaeological objects, sending staff members into the field, and hiring agents to amass collections. Beginning in the 1970s, in response to Indian protests, many slowly began to incorporate contemporary native perspectives into exhibitions of artifacts. Anthropologists, many of whom also worked as political activists on behalf of Indian tribes, were a critical element in passing the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978. They and others continue their advocacy on behalf of Indians.

Recently, Native Americans have won validation for their claims to cultural patrimony and interpretation. The Native American Graves and Repatriation Act of 1990 gives tribal members the right to reclaim religious or significant cultural artifacts from the museums or individuals who hold them. And the National Museum of the American Indian, which opened in Washington in 2004, provides native people with a new platform for disseminating the message of Native American achievement.

Edward H. Davis. Field Notes and Sketchbooks, 1910-1929.

Edward Davis (1862-1951), an indefatigable collector who lived near Mesa Grande outside of San Diego, amassed a significant collection of ethnographic objects from southern California for George G. Heye’s Museum of the American Indian in New York. His notes and sketchbooks document his experiences with the Mesa Grande (Diegueño) Indians, and others in the area. He also traveled to Mexico, visiting the Seri Indians of Tiburon Island, and the Opata and Yaqui Indians in Sonora. This sketch and notebook from a 1922 trip is of a guqui, a house for making the palm fiber hats worn by many Opata men. It was constructed partially underground to keep the fibers moist for weaving.

F. H. Cushing. Daily Report of Hemenway Southwestern Archaeological Expedition. March 4, 1888.

The Hemenway Expedition, named for its patron, Mary Hemenway, was the first major scientific archaeological investigation in the Southwest. Its controversial director, Frank Hamilton Cushing (1857-1900), was already known to the world as the man who had lived with the Zuni Indians. The expedition (1886-1894) was plagued with problems, including the health and erratic behavior of its director. Today, scholars are reevaluating the significance of Cushing’s ethnographic work and the role of the Hemenway Expedition in the history of American anthropology.

Camp Hemenway, the site of this “Daily Report,” was located nine miles southeast of Tempe in Arizona Territory. In its accompanying sketches, Cushing compares objects from the nearby Los Muertos and Los Guanacos archaeological sites, with contemporary work from Zuni Pueblo and objects from China.

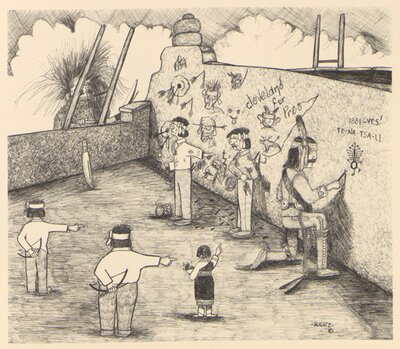

Phil Hughte. A Zuni Artist Looks at Frank Hamilton Cushing. Zuni, NM: Pueblo of Zuni Arts & Crafts, A:Shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center, 1994.

The author reverses standard anthropologist-Indian roles in this book of tongue-in-cheek cartoons that gently mock Cushing’s life, both at Zuni (1879-1884) and afterwards. Here, he refers to Cushing’s elevation to Bow Priest of the Warrior Society, a position of leadership in Zuni society.

Samuel Kirkland Lothrop. Chile notes, vol. 2, 1929.

Lothrop (1892-1965), who devoted his career to the study of Latin America, was a member of the Museum of the American Indian’s large staff of anthropologists in the 1920s. He spent a year in Chile under the auspices of the Thea Heye Expedition, conducting archaeological research in the western foothills of the Andes and collecting Araucanian artifacts. The page of his notebook shown here depicts a loom of the Chilote Indians, known for their elaborate textile designs.

Clarence B. Moore. Notebooks. Mandarin Point, Duval County, St. John’s River, Fla., Nov. 4, 1893.

Clarence B. Moore (1852-1936) was a wealthy amateur archaeologist from Philadelphia who crisscrossed the rivers of the southeast each year in his steam-powered paddleboat, the Gopher, excavating sites near the shores in states ranging from Alabama to Tennessee. During his twenty years of investigations, Moore explored an astounding number of archaeological sites. He published the results of his investigations regularly, translating the field notes he kept in small journals into the larger, neatly written notebooks that he later used as the basis for his publications.

During his excavations, Moore uncovered many artifacts associated with Indian burials that later ended up in museums. These artifacts are now subject to repatriation by tribal members working to reclaim their sacred heritage. Natives and non-natives alike rely on Moore’s “Field Notes,” which can provide important clues about the history of an artifact, helping to further repatriation claims.