European Encroachment, Native Resistance

As European colonists and their successors moved relentlessly westward, they forced Native Americans to relinquish their traditional lands, and with it, their sovereignty. The struggle for land is a major theme in Native American history.

Diplomatic accords, brokered to avoid impending crisis rather than to establish lasting agreements, invariably collapsed in the face of settlers’ demands for more space. Indians responded to broken treaties with a combination of retreat, strategic alliances with European rivals, and armed resistance. The American colonists’ victory in the War of Independence presented Native Americans with a single expansionist power, intent on continental domination.

All forms of native resistance proved ineffective. The Cherokees gained no relief from their successful appeals to the Supreme Court. And fierce armed resistance from Plains tribes, even their resounding victory at the Little Bighorn, would not prevent settlers and miners from entering their territory. The tragic confrontation at Wounded Knee in 1890 marked the end of large-scale armed resistance by Native Americans.

Receipt Signed by Geronimo for Work as a Policeman. Fort Sill, Indian Territory, July 1896.

Geronimo (1829-1909), a Chiricahua Apache war chief, and his followers fled to Mexico when the Americans decided to move the Chiricahuas from their home at Apache Pass to the San Carlos Reservation in 1876. For the next eleven years he raided settlements along the Mexico-United States border, his name striking fear in local communities. Finally arrested by General George Miles in 1887, he and 340 members of his band were imprisoned first at Fort Marion, Florida, then at Mount Vernon Barracks in Alabama. Eventually, many were taken in by the Kiowas and Comanches, former rivals, on their reservation at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where Geronimo worked at times as a justice of the peace and as a police officer. He attended the St. Louis World’s Fair, and rode in Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade. Never allowed to return to Arizona, he died of pneumonia in 1909.

Treaty of Peace with the Delaware Nation, July 1765.

The treaty of peace that William Johnson, Superintendent of Indians for the British Crown, signed with the Delawares (Lenni Lenape) in May 1765, codified the end of their participation in the Ottawa leader Pontiac’s 1763-64 rebellion against the British. This addendum to the treaty was added to secure the submission of the Ohio Shawnees and Mingos. The end of the French and Indian War earlier that year left his Ottawa (Odawa) territory in the Great Lakes area under British supervision, and helped spark Pontiac’s uprising. Pontiac and the Ottawas, backed up by Wyandots (Wendat), Potawatomis, and Chippewas (Anishinaabe), besieged the fort at Detroit, while his Delaware (Lenni Lenape), Mingos (Seneca-Cayuga), and Shawnee allies overwhelmed many British outposts, including Sandusky, Michilimackinac, and Presque Isle. The eastern allies were subdued during Colonel Henry Bouquet’s 1764 Ohio campaign. The 1765 treaty codifies the Indians’ capitulation. Pontiac, himself, signed a separate treaty with William Johnson in 1766 and was pardoned by the British.

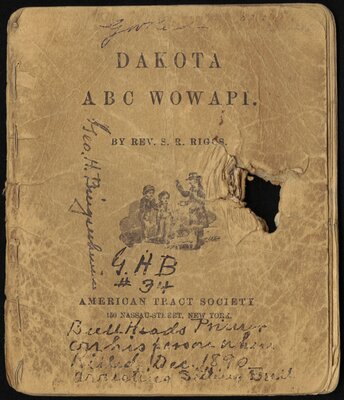

Bullhead’s Primer. December, 1890.

Bullhead was one of the officers of the Indian Police sent to arrest Sitting Bull (ca. 1831-1890) at his home on the Standing Rock Reservation on December 15, 1890. U. S. government Indian agents, alarmed by the spread of the messianic Ghost Dance movement, believed the incarceration of Sitting Bull would stem a feared uprising. The famed Lakota war chief and medicine man appealed to his followers for assistance, and was shot and killed by Bullhead and Red Tomahawk when they tried to arrest him. Bullhead died during the melee that ensued. A few days later, the tragic massacre at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation effectively ended both the Ghost Dance movement and armed Indian resistance. This Dakota language primer was reportedly found on Bullhead’s body.

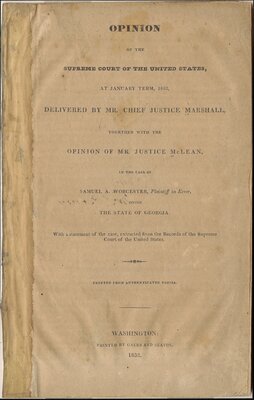

U. S. Supreme Court. Opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States...1832...in the case of Samuel A. Worcester, plaintiff, ...versus the State of Georgia.

This case, prelude to the infamous forced Cherokee Removal from Georgia and the Carolinas in 1838, upheld the Cherokee assertion that the federal government, not the states, had jurisdiction when dealing with Indian tribes. When the State of Georgia did not comply with this decision, however, President Jackson did nothing to enforce it. Unable to reach an agreement for removal with the elected Cherokee government, the U. S. signed a treaty with a dissident faction in 1835. The treaty was quickly ratified by Congress and upheld despite a petition signed by more than 15,000 Cherokees denying its legitimacy.

Alexander Gardner. Photographs of Red Cloud and Principal Chiefs of Dacotah Indians. Washington: Gibson Bros., [1872].

Red Cloud (ca. 1821-1909) was a powerful leader of the Lakota. Incensed by the number of settlers crossing Indian territory, he coordinated successful military and diplomatic initiatives against forts that the U. S. Army was constructing to protect the Bozeman Trail. A reluctant military complied, and the resulting Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 established the Great Sioux Reservation. While in Washington in May 1872 to speak with President Grant, Red Cloud and his delegation were photographed by Alexander Gardner, the famous Civil War photographer.