Getting into Print

Lady Novelists & Their Publishers

These letters provide insight into the relationships between female authors and their male publishers and editors. Written by a number of novelists to the London publishing firm George Bentley and Son, the letters reveal how the authors carefully, yet boldly, negotiated their way through the editorial and publishing process in an environment that frequently devalued women’s writing.

Although women did not have uniform experiences in their literary business dealings, these letters show them to be active managers of their own careers and keen advocates for their reputations and financial interests.

The letters address issues of editorial revision, copy-right, book design, contract royalties, printing, and advertising, and sometimes illuminate tensions over issues of control and authority in decision making.

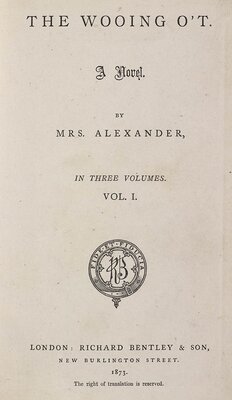

Mrs. Alexander 1825-1902

Annie Hector, who published under the name of Mrs. Alexander, wrote several novels during her marriage; but her husband, the explorer Alexander Hector, disapproved of her writing. After his death in 1875, she used his first name as her pseudonym and published over forty novels.

Many female writers pointedly employed their married honorific as part of their pen name–a strategy calculated to side-step the social stigma attached to "scribbling old maid." Marriage also implied that their writing was motivated by feeling rather than financial necessity, a concern for women anxious to maintain the appearance of leisured-class status.

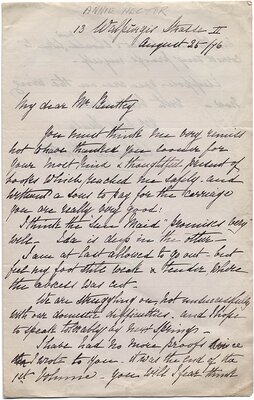

In her letter to George Bentley Mrs. Alexander thanks him for the present of some books and admires The Sun-Maid (by Maria M. Grant). She asks what has happened to the proofs for her Heritage of Langdale, before noting: "You will I fear think me whimsical but I should now like to correct my proofs myself."

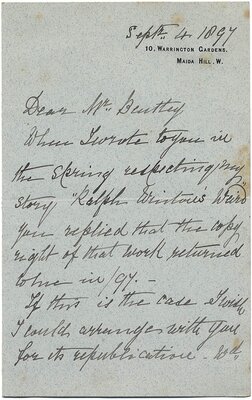

In her letter to Richard Bentley she notes that the copyright of Ralph Wilton's Weird has now reverted to her, and wonders whether he would be interested in republishing it and on what terms. Her last line, "I shd like still to sail under the old colours," refers to the continued use of her pseudonym.

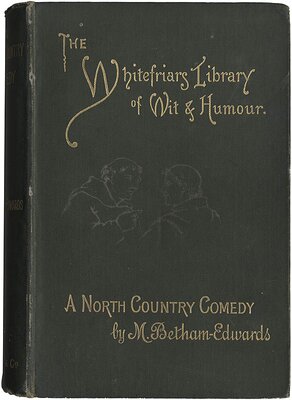

Matilda Betham-Edwards, 1836-1919

Miss Betham-Edwards hyphenated her name to include her mother's maiden name. In her sixty-two years as an active writer, she wrote dozens of novels, children's books, and books about France. After her father's death in 1864, she moved to London and became a prominent member of the London literary world; her friends included George Eliot, Coventry Patmore, and Sarah Grand.

Bentham-Edwards visited France for the first tiem in 1875. Over the next forty years, She published multiple works on the political sympathies, econ-omic conditions, and regional characteristics of nearly every part of France.

Before her death she was granted the honor of a civil list pension by the British government. But the crowning achievement of Betham-Edwards's life came in 1891, when France awarded her the title of Officier de l'Instruction Publique de France.

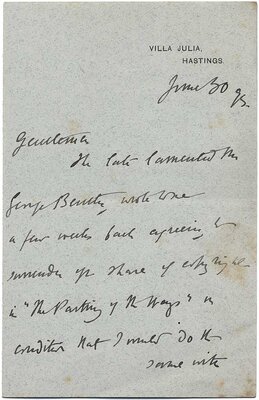

The first of these two letters refers to a recently submitted unidentified work (probably The Roof of France), which she hopes Bentley's reader enjoyed. She says they will have no difficulty in coming to terms, but she suggests delaying a decision to serialize the story in the magazine Temple Bar. The second letter refers to a discussion with "the late lamented George Bentley" over surrendering the Bentley share of the copyright of her novel The Parting of the Ways, and asks how many copies are left in stock.

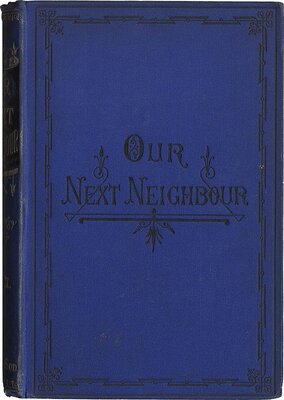

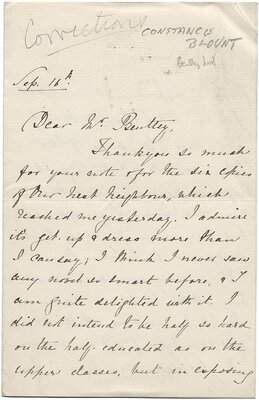

Courteney Grant, fl. 1873-1882 [pseudonym of Constance Blount]

Constance Blount wrote five novels, of which Our Next Neighbour was the third.

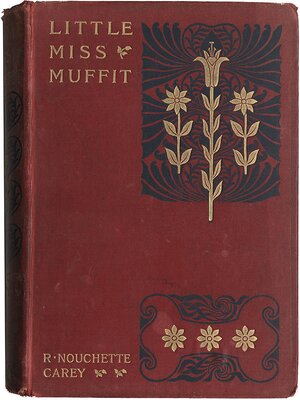

In Blount’s first letter she expresses her delight with the cover design of her novel Our Next Neighbour, and its binding ("I think I never saw any novel so smart before..."). About the book she observes: "I did not intend to be half so hard on the half-educated as on the upper classes, but in exposing... the sins of the latter, one c'd not... refrain from showing the more ridiculous & disagreeable but less serious faults of those supposed to be below them."

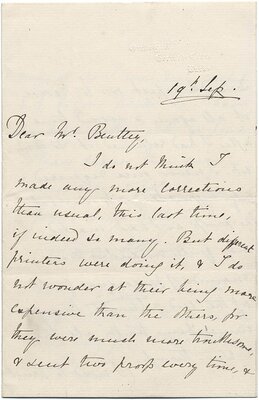

Her second letter deals with the growing disagreement between Bentley’s and Clowes & Clowes, the firm that printed Our Next Neighbour. Bentley is not happy with the price the printers have charged for making author's corrections. She complains about Clowes: "I do not wonder at their being more expensive than the others [printers], for they were much more troublesome." She argues that she did not make many changes and as she used to print herself, she was "very careful not to give trouble."

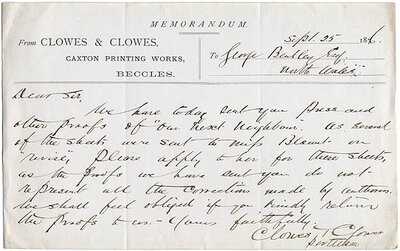

Printing Dispute over Our Next Neighbour

This letter and memorandum was sent to Bentley’s from the printers Clowes & Clowes, in the hope that Bentley’s would understand why Clowes had to charge so much for press corrections to Blount’s novel Our Next Neighbour. Clowes points out that the author made corrections without regard to expense, and ignored "simple directions."

Berthe Henry Buxton, 1844-1881

At the age of sixteen, Berthe Buxton married Henry Buxton, a club manager and occasional writer. After fifteen years of marriage he became bankrupt and deserted her and her children. She turned to the stage and writing in order to support herself. In many of her novels she argues in favor of the "much-abused stage." Her novels feature strong female characters, and recurrent themes include English-European relations and blindness; she collaborated several times with the blind author W. W. Fenn.

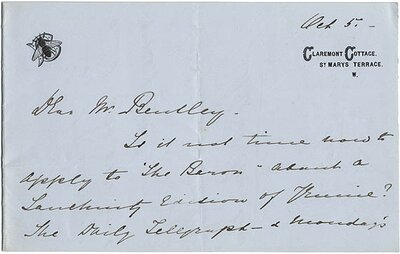

In this letter, Buxton tells Bentley of favorable reviews of her* Jennie of ‘The Prince’s’* and asks for confirmation that 500 volumes of the first edition were sold. She suggests that she should contact "the Baron" directly about a Tauchnitz edition of Jennie and asks Bentley for advice on how to approach the subject.

Rosa Nouchette Carey, 1840-1909

Rosa Nouchette Carey wrote about forty novels, many of which achieved great popularity. Her fiction focused on domestic and family themes, and her plots and characters generally reflected a conservative outlook. In her youth, Carey tried to quench her longing to write, believing that it was impossible to combine literary achievement with a useful domestic life. But her writing won out, and she never married. Although her literary reputation was not high, her works sold well, remaining in print from 1868 until 1924.

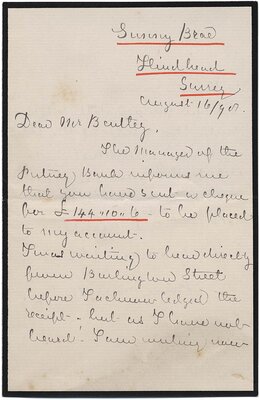

These letters, concerning Carey’s financial relationship with Bentley's, belie the stereotype of the frivolous lady scribbler. Insead, they show an assertive, business-minded author negotiating confidently with her publisher. Carey requests increased royalties ("one penny in the shilling") and stands her ground when Bentley offers her much less than she had asked for. Reminding Bentley of her long career as a novelist and her good reputation, she notes that she is "one of the most popular & steady selling writers of the present day." She complains about the timing of the cheap edition of her novel The Old Old Story. She also acknowledges receipt of 144.10.6 for her work.

Mary Cholmondeley, 1859-1925

Mary Cholmondeley was born in Shropshire in 1859, the eldest daughter of a vicar. Early on she was forced to assume management of household and parish duties when her mother became ill. After her mother's death, Cholmondeley continued to live at home, caring for her father until he died in 1910. She remained unmarried.

Cholmondeley found liberation from her family responsibilities in her writings. In 1877, she wrote in her journal, "What a pleasure and interest it would be to me in life to write books. I must strike out a line of some kind, and if I do not marry (for at best that is hardly likely, as I possess neither beauty nor charms) I should want some definite occupa-tion, besides the home duties." She went on to write more than 15 novels.

Cholmondeley was introduced to George Bentley, who published three of her novels, by her friend the successful novelist Rhoda Broughton.

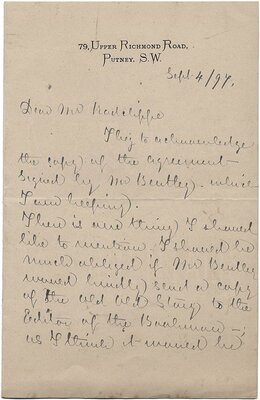

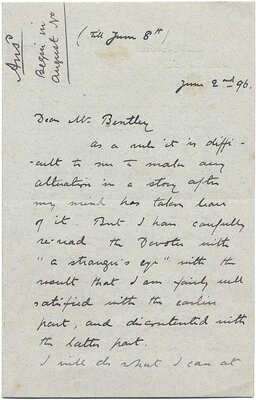

In this letter, she discusses her novel A Devotee: An Episode in the Life of a Butterfly. The work was serialized in Temple Bar from August to October 1896. The letter concerns the revisions she has been making to the novel. She finds it difficult to go back to a story after she has stopped thinking about it, but admits the second half needs reworking. She makes several suggestions but adds, "Please forgive me beforehand if the story proves obstinate."

Mary Cholmondeley’s most famous work, Red Pottage, made her reputation. Within two months of its initial release, the book had sold more than 18,000 copies in England alone.

Despite the book’s great success, however, the author received little money for it because she had sold the copyright. Cholmondeley was also clearly conflicted about her new-found literary celebrity: "I have not written a word since January," she noted in her journal that year. "But what a pity–just this year of all years to have written nothing when so much has been happening, when I am positively and actually that monster 'a celebrity,' which I may not be next year."

Red Pottage provides a powerful illustration of English provincial life, and of the limited opportunities available to unmarried women in the late nineteenth century. Published in a new edition in 1985 with an introduction by feminist critic Elaine Showalter, Red Pottage was resurrected at the end of the twentieth century as one of the most innovative and radical of New Woman novels.

Henrietta Anne Duff, 1842-1879

Henrietta Duff was the daughter of Vice-Admiral Norwich Duff. A lifelong invalid, she died of heart disease at the age of thirty-seven. Duff wrote three novels and a volume of verse. *Virginia, *a love story about an English sculptor, was the only one of her four works to be published in her lifetime.

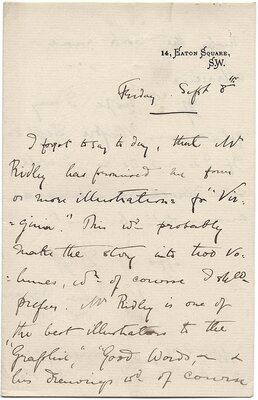

Duff's letter concerns the acceptance and publication of her novel Virginia, 1877. She suggests that the book could be illustrated by Mr. Ridley, describing him as "one of the best illustrators to the ‘Graphic,’ ‘Good words,’-& his drawings wd of course make the work much more attractive." She mentions that she would like Virginia to be published in two volumes, which did not happen, but the one volume edition included four interesting etched plates by Ridley.

Frances Mary Peard, 1835–1922

Mary Peard wrote books for both adults and children. She was well travelled, and several of her novels are set in foreign countries. Her closest friend was the novelist Christabel Coleridge. She apparently never married.

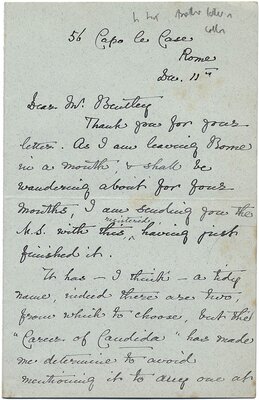

The letter refers to Peard's Donna Teresa, which was published by Macmillan in 1899, after it bought Bentley's. She is guarded about suggesting her alternative titles, having had a bad experience with her Career of Claudia. She discusses the length of Donna Teresa in relation to Temple Bar and asks Bentley for his offer to purchase the story, including American and Colonial rights.

Charlotte Elizabeth Riddell, 1832–1906

Charlotte Elizabeth Lawson Cowan was born in 1832 in a small town near Belfast. When her father died, she and her mother were left with limited means. Unable to survive in such reduced circumstances, they decided to move to London, where Charlotte might earn a living as a writer.

After her mother’s death in 1857, Charlotte married Joseph Hadley Riddell, a civil engineer. When he died in 1880, leaving her with substantial debts, she increased the output of her pen to pay them off. Like many of her female writer contemporaries, Riddell–the author of more than 50 novels and stories–was the chief support for the household. She had no children.

Riddell was one of the first women to write fiction about London City life and the world of business. She also wrote children’s stories, tales of her native Ireland, and supernatural tales. In 1868 she became part owner and editor of St. James's Magazine.

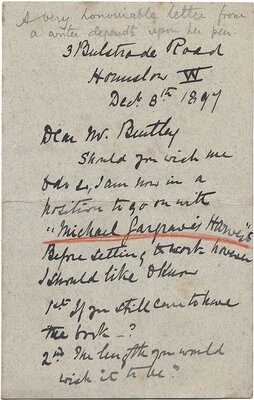

This letter concerns Riddell’s work, A Bid for Fortune; or, Michael Gargrave's Harvest, which is listed in the Bentley Private Catalogue for 1898 but was never issued. The publishing agreement for the work was signed in 1894, but not until December 1897 does Mrs. Riddell write that she is ready to "go on" with it. Before she does, she wishes to know if Bentley still wants to publish the novel, whether she should change the hero's name, and how long the book should be. She is aware of the major changes in the publishing world (negotiations were being made with Smith Elder for the sale of Richard Bentley and Son at that time, but it was sold to Macmillan in 1898) and realizes that this may affect the publication of her novel. She feels it is her fault for not getting the manuscript to Bentley earlier, and does not want him to feel anxious about breaking their agreement. A pencilled note from the publisher comments: "A very honourable letter from a writer dependent upon her pen."

![Autograph letter [ca. 1888]](https://exhibits.library.cornell.edu/images/10286-35a5d6d2ad611ebc1521ca00ba724147/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)

![Phemie Keller. A novel . By F.G. Trafford [pseud.] ...](https://exhibits.library.cornell.edu/images/10262-0f184de5d9283fe335efce0c986af24d/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)