Television

"I don't give advice. I can't tell anybody what to do. Instead I say this is what we know about this problem at this time. And here are the consequences of these actions." - Dr. Joyce Brothers

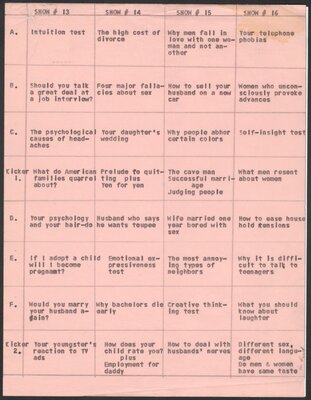

Consult Dr. Brothers

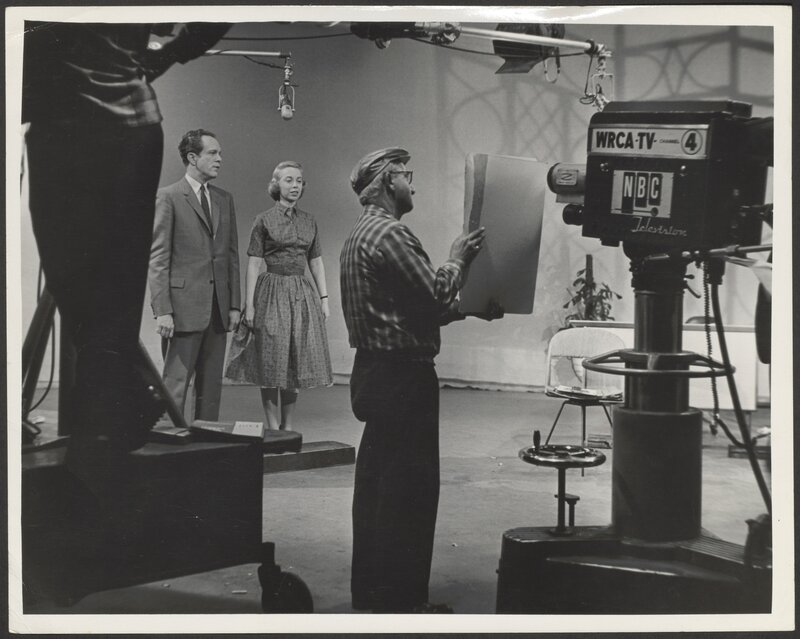

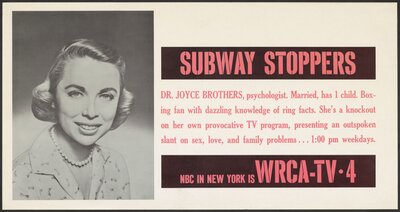

Following her popularity on The $64,000 Question, the glowing reception of her first book, and numerous public appearances, the natural next step for Dr. Brothers was her own television show. According to an interview questionnaire for TV Radio Mirror, Dr. Brothers began preparing an educational psychology television program with the Metropolitan National TV Association. She suggested to WNBC that it might be suitable for a commercial station, and so began her first program in 1958 with the local New York station, WRCA-TV. The name of her show changed from The Dr. Joyce Brothers Show to Consult Dr. Brothers, but the format remained the same: Brothers would read letters from viewers aloud, then offer general advice. Sometimes she would present new research or discuss the findings of a recent survey. The first iteration of the show featured an assistant, Roger Tuttle, who would read the letter to Brothers, and then she would discuss the problem. Consult Dr. Brothers brought, for the first time, relatable and compassionate advice into the comfort of one's living room. Though deemed too crude and inappropriate by many critics, the show—and especially the calm, soothing presence of Dr. Brothers—was a rousing success.

The Dr. Joyce Brothers Show. “Showing son too much affection,” episode unknown, circa 1958.

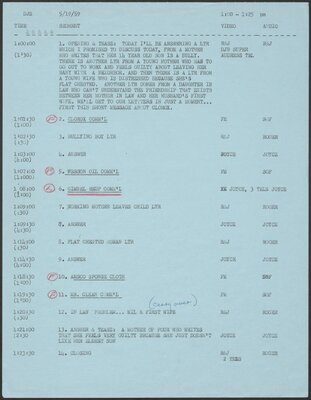

Consult Dr. Brothers. “Tattooed men,” Episode 4, circa 1959.

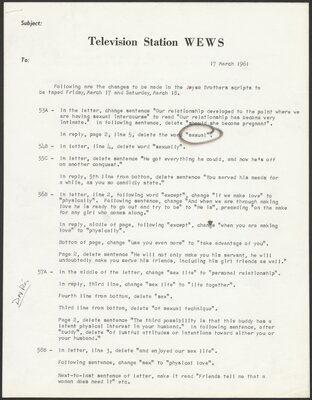

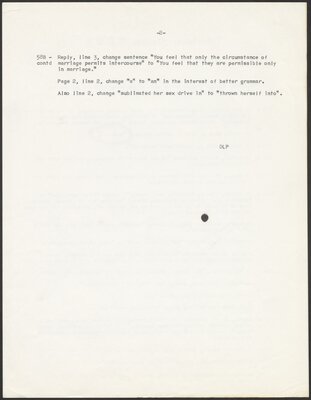

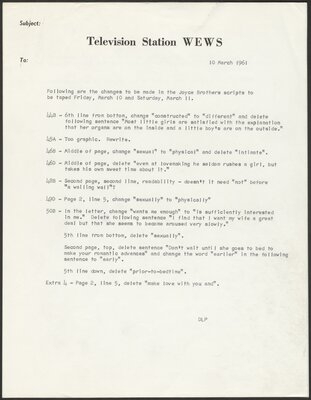

Redactions for the script Consult Dr. Brothers from WEWS, 1961.

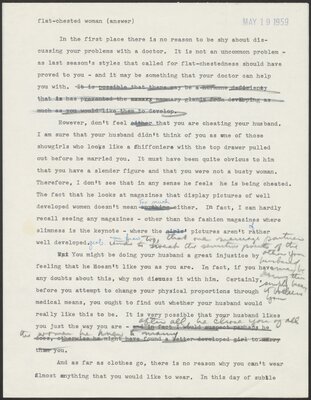

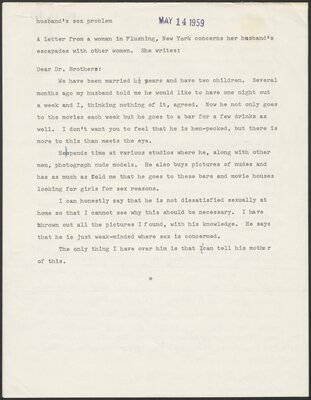

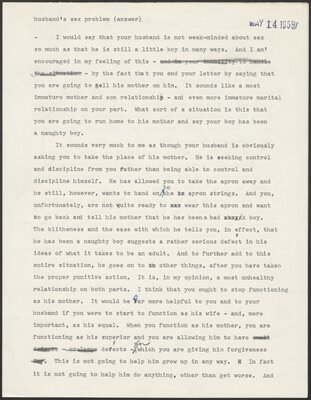

It may come as no surprise that letters from readers were vetted by the station and sometimes censored to use language appropriate for the time. Dr. Brothers kept this correspondence in her records. Note the frequent deletion or alteration of the word “sex” and its variations. One edit even changed the original “former boyfriends” to “ex-husband.”

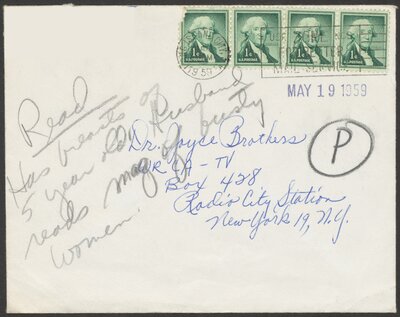

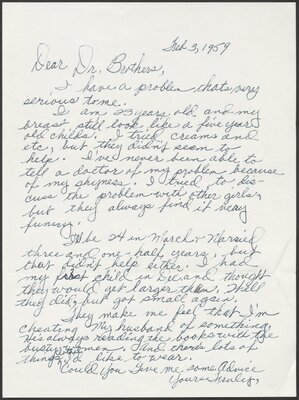

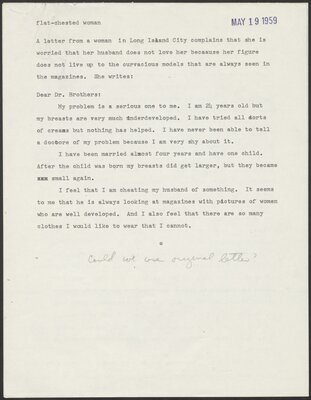

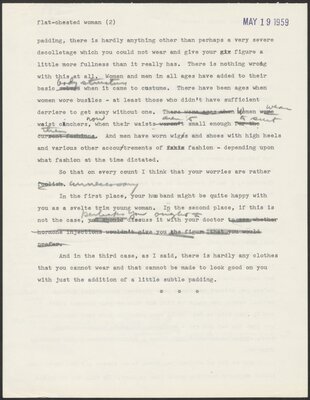

Consult Dr. Brothers script with original letter, “flat-chested woman” segment, 1959.

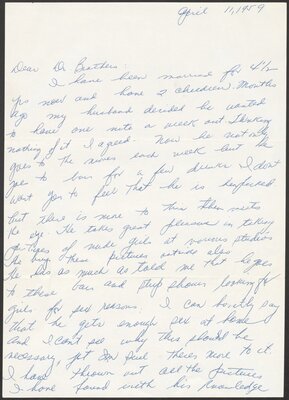

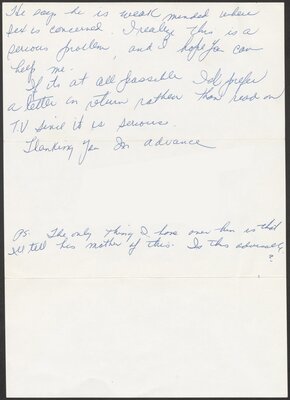

Dr. Brothers received thousands of letters from viewers, and she and her team chose which would be read on her show. She would write up a segment offering her advice on the situation, which would make its way through the script-writers and television censors. She kept each iteration of this work together in a folder, one folder per episode. This is an example of the lifecycle of a letter to be read on television: first, Dr. Brothers received the letter, and a version was typed, with spelling errors and grammar corrected for easy reading. Sometimes portions of the letter would be left out if they were deemed unimportant or repetitive. Then, Dr. Brothers wrote her opinion and advice on the matter. Finally, the station sent their edits and redactions, oftentimes differing dramatically from the original letter and Dr. Brothers' advice. Though the viewer’s issue remained the same, details and innuendo were frequently lost during this process.

Personally identifying details have been omitted.

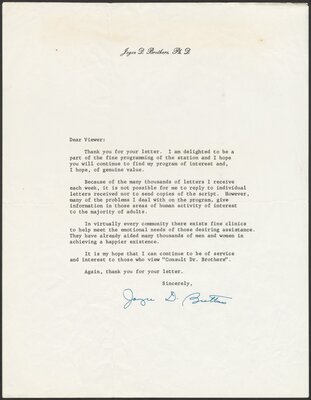

Brothers’ response mailed to viewers who wrote letters to her, undated.

Brothers states that she is not able to offer specific medical recommendations, but can speak broadly on the topic.

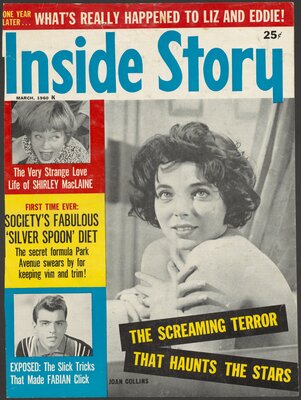

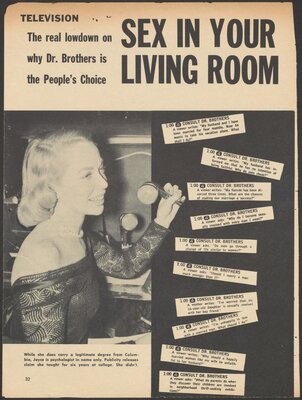

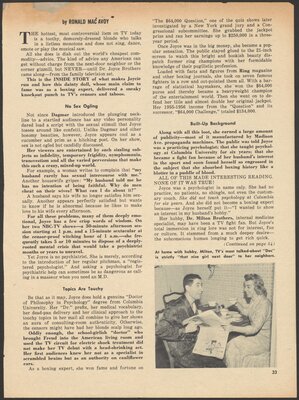

Inside Story magazine. "Sex in your Living Room" article, March 1960.

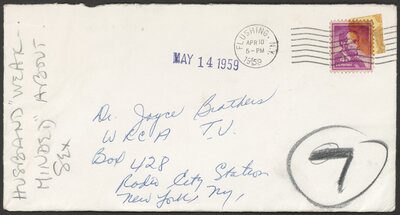

Consult Dr. Brothers script with original letter, “husband sex problem” segment, 1959.

Personally identifying details have been omitted.

Dr. Brothers’ Emmy Award nomination for “Most Outstanding Female Personality” for her show Consult Dr. Brothers, May 6, 1959.

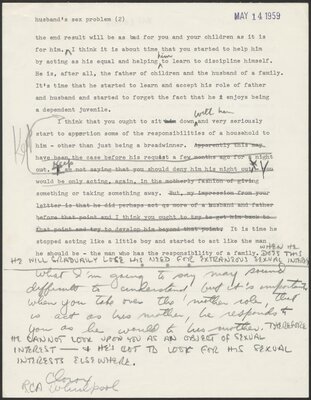

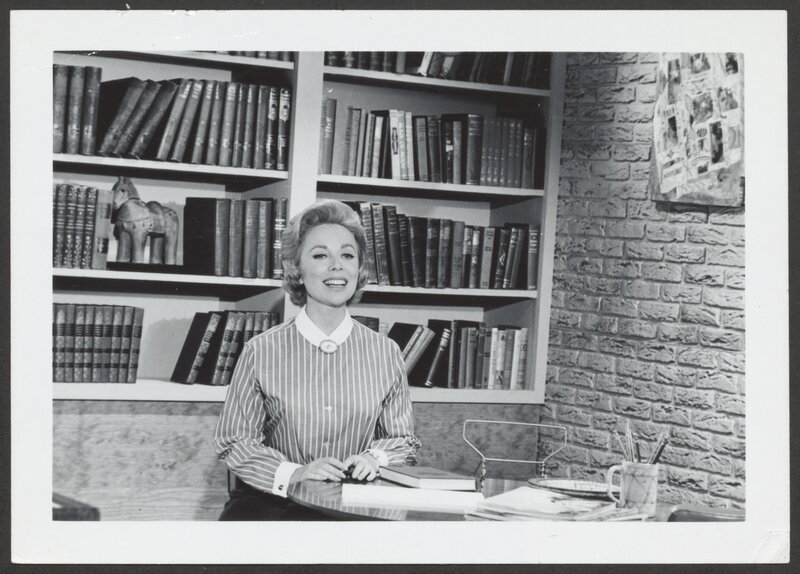

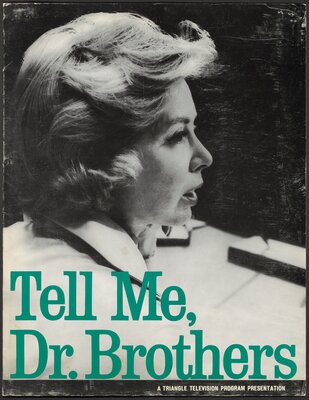

Tell Me, Dr. Brothers

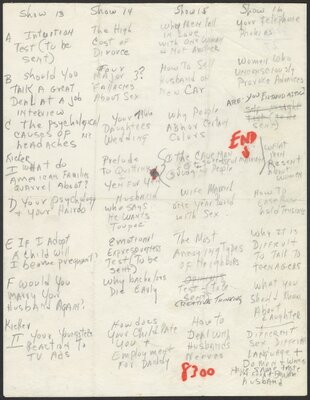

The next iteration of Dr. Brothers’ show, titled Tell Me, Dr. Brothers, mirrored Consult Dr. Brothers significantly. Many of the scripts for the former are covered with markings from the latter. Tell Me, Dr. Brothers began filming in 1962, with 39 half-hour episodes in black and white and 130 episodes in color. Dr. Brothers wandered around the set, reading letters from viewers and offering her advice. Inserted among the letters and responses was a “research capsule,” where she discussed a recent finding in the medical, psychological, or sociological fields, and offered her opinion. Almost every episode presented a quiz to the viewers: How vain are you? How empathic are you? Are you an introvert or an extrovert? One even presented a Rorschach-style test and discussed the differences between what males and females see in the abstract images. During the early to mid-1960s, millions of viewers would tune in to watch Dr. Brothers twice a day, five days a week, in addition to listening to her almost daily on the local New York radio.

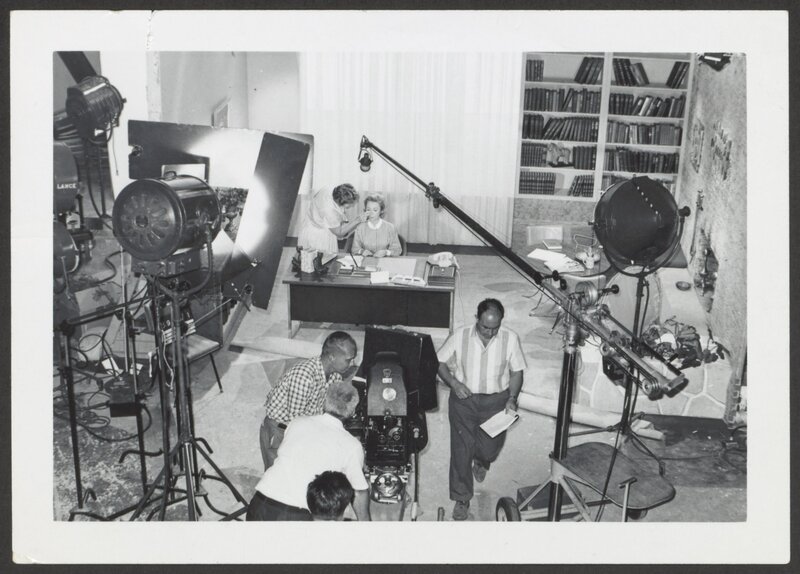

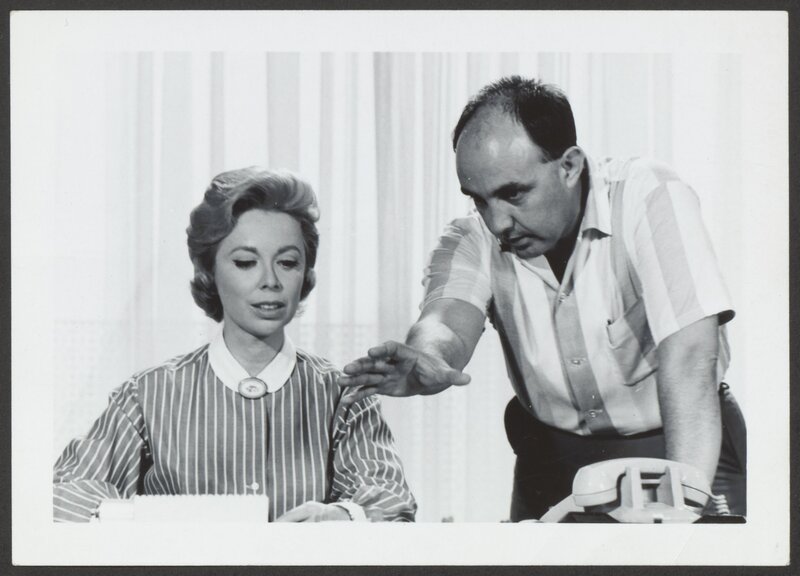

Tell Me, Dr. Brothers. Promotional film, circa 1965.