The Emancipation Proclamation

After the Union won the battle of Antietam in 1862, Lincoln issued a presidential decree to the Confederate states, declaring that he would free all slaves in Southern states if they did not surrender and rejoin the Union. The Confederacy rebuffed his ultimatum, and on January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation.

Some believe that the Emancipation Proclamation abolished slavery, while others claim that Lincoln’s presidential decree was impotent, freeing no one. Both viewpoints are flawed. The Emancipation Proclamation decreed the end of slavery in all states that had seceded from the Union. When they heard about the order, slaves from rebellion states started a mass exodus to Union soldier lines. However, the Proclamation did not end slavery in slave states that had remained loyal to the Union, or in territories of the Confederacy that had been reconquered. The Emancipation Proclamation also permitted blacks to fight as Union soldiers against the rebellion states. Ironically, Lincoln had previously refused to let blacks serve in the army, even though they had a vested interest in a Union victory, and even though the Confederacy had commonly used forced black labor to assist Rebel troops. Lincoln had kept blacks out of the army in an effort to pacify loyal white Southerners and Northerners who wanted to uphold America’s racial caste system.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation depended on a Northern victory for its enactment, and some slaves were not informed of their freedom until months later, it nonetheless pierced the heart of the South. It changed the war’s focus from preserving the Union to ending slavery, and opened a path for the actual abolition of slavery in the United States.

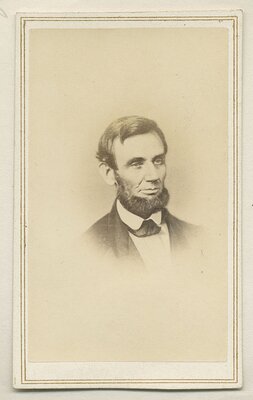

Abraham Lincoln

In a nation where the South clung to slavery and the majority of the North was against abolition, Lincoln was forced to walk a dangerous tightrope. Personally, Lincoln loathed slavery and the contradiction it posed to America’s founding ideal of liberty. Finding it difficult to reconcile these opposing principles and satisfy everyone, he embraced gradual abolition, African colonization of slaves, and financial compensation for slave owners. He reasoned that while Southerners might free their slaves, white prejudice made it impossible for blacks and whites to coexist successfully in the same society.

However, with constant pressure from abolitionists, beleaguered Union troops, and the South’s absolute refusal to end slavery, Lincoln’s thinking and policy began to evolve. Perhaps he knew that putting an end to slavery was the only way to save the Union. Whatever the reason, he did what all of his predecessors had failed to do: he upheld the integrity of the United States’ founding principles by beginning to legally dismantle slavery.

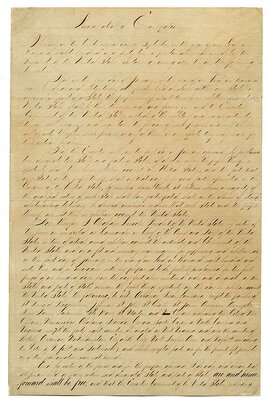

Shown here is the first engrossed copy of the Emancipation Proclamation made from the manuscript draft that was sent to the State Department.

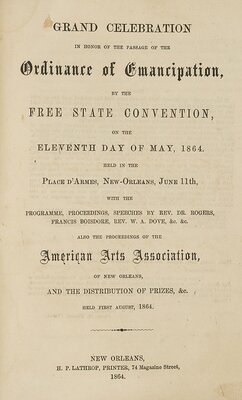

Grand Celebration

Slaves were jubilant when news of the Emancipation Proclamation spread, and spontaneous celebrations broke out. Until that moment, many slaves did not believe that they would ever experience freedom in their lifetimes. This pamphlet commemorates the one-year anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation by black communities in the city of New Orleans.